Firms like Form Energy and Ore Energy are deploying iron-air technology to solve the renewable energy storage problem, keeping grids powered for longer

“The most exciting clean tech innovation of 2025? It might just be rust.”

That is the assessment of Mark Loveridge, Commercial Director of Renewable Exchange. But Mark’s enthusiasm doesn’t have anything to do with old bike chains or an oven in need of a deep clean.

Instead, people like Mark are getting very excited about the role that rust could play in mitigating climate change.

The problem with renewable energy systems as things stand is, unlike fossil fuels, renewable energies like solar and wind are difficult to store in the quantities we need.

This means that when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow, energy supplies run low.

The renewable energy storage problem

For decades, the energy storage conversation has been ruled by the lithium-ion cell, a technology that powers everything from our mobile phones to electric vehicles.

But with 2025 drawing to a close, a chemically distinct contender has emerged from the laboratory to the electrical grid.

“After decades of dominance by lithium-ion, 2025 is potentially the turning point for long-duration energy storage (LDES), and iron-air batteries are leading the charge,” Mark says.

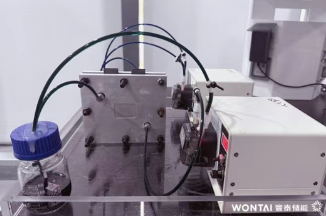

The premise is elegantly simple, in the way that the world’s best inventions often are. These batteries harness the process of reversible rusting.

During discharge, the battery “breathes” in oxygen from the air which converts iron pellets into rust and releases energy.

To charge, an electrical current turns the rust back into metallic iron and the battery “exhales” oxygen.

The unique capabilities of iron-air batteries

The primary limitation of lithium-ion technology is its duration.

While excellent for short bursts of power lasting two to four hours, lithium-ion becomes prohibitively expensive when trying to bridge multi-day gaps in renewable generation.

This is where iron-air technology finds its niche.

“They’re capable of storing energy for 100+ hours – enabling wind and solar to keep the lights on, even when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow,” Mark explains.

By offering a duration that is orders of magnitude longer than conventional batteries, iron-air systems can replace fossil fuel peaker plants.

“Ideal for grid-scale decarbonisation, especially during multi-day renewable lulls,” Mark adds.

From theory to practice

The technology has moved rapidly from theoretical models to concrete infrastructure this year.

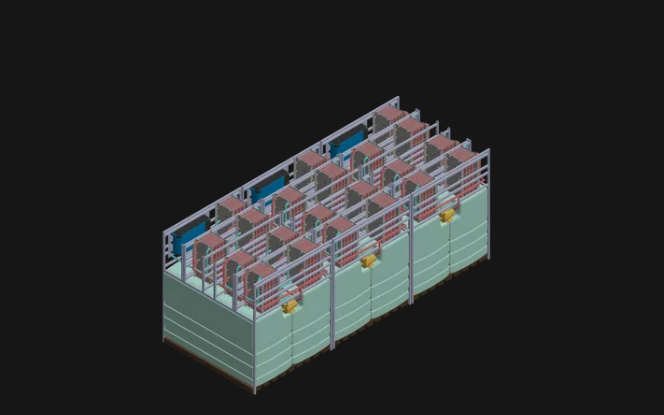

“This year, Ore Energy in the Netherlands delivered the world’s first grid-connected iron-air battery, and Form Energy in the US raised over US$400m to bring this tech to commercial scale,” Mark says.

The Ore Energy pilot, connected to the grid in Delft in July 2025, represents a crucial proof of concept for the European market.

It demonstrates that these systems can be integrated safely into dense urban environments.

Across the Atlantic, Form Energy has operationalised its commercial-scale factory in Weirton, West Virginia, on the site of a former steel mill.

The company is currently fulfilling orders for major utilities, including Xcel Energy and Georgia Power, with projects expected to come online in late 2025 and 2026.

The geopolitics of abundance

Beyond the technical specifications, the iron-air battery offers a significant geopolitical advantage.

The transition to clean energy has often meant trading a dependency on fossil fuels for a dependency on rare earth minerals like lithium, cobalt and nickel – all of which are growing scarcer and more contested.

Iron-air batteries sidestep this scarcity trap entirely as they are made using only abundant, inexpensive materials – iron, air and water.

This abundance translates to stability and security for national energy strategies, reducing conflict and streamlining supply chains.

What’s more, the environmental profile of these batteries aligns closely with circular economy principles simply because their active materials are non-toxic and easily recyclable at the end of the system’s life.

A heavyweight contender

It is important to note that these batteries are not designed to be used in EVs or smartphones.

They are also heavy, bulky and relatively inefficient compared to their lithium counterparts.

However, for a static asset sitting on a concrete pad next to a wind farm, these batteries could be perfect.

The cost per kilowatt-hour is the deciding factor and iron-air targets a price point less than US$20/kWh, a fraction of the cost of lithium-ion.

This economic efficiency allows utilities to store vast amounts of energy without bankrupting the grid.

More importantly, pivoting away from rare earth minerals frees those resources up for use in climate technologies where there are no other alternatives.

As we look to the future, it is possible that the reliable, sustainable power grids we are looking for may well be built using the most common metal on Earth.

“For those watching the future of energy: keep an eye on iron-air,” Mark says.

“It’s not just innovative, it’s potentially transformative for the sector.”